WICHITA, Kansas. — In Wichita, public frustration with infrastructure is a tale of two cities, embodied by two persistent, high-profile bottlenecks: a downtown bridge that shears the tops off trucks and a rail corridor that holds north-side commuters hostage.

On the surface, both problems appear to stem from the same issue: a lack of official concern. However, a deeper investigation reveals two vastly different stories.

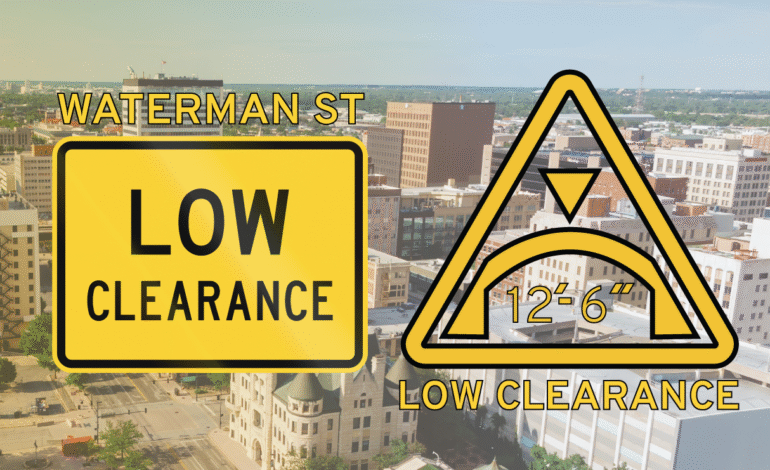

One is a problem of will. The city’s infamous 12-foot-clearance bridge on Waterman Street, a “truck-killer” that provides endless online fodder, is met with what appears to be a deliberate policy of tolerance.

The other is a problem of scale and law. The gridlock on the north side, where trains block vital crossings for hours, is not ignored. Rather, it is an intractable legal battle mired in federal preemption and an engineering challenge with a staggering $100 million price tag.

While residents see two equally infuriating problems, city and state officials are fighting two entirely different wars—one they are choosing not to wage, and one they are legally barred from winning outright.

Case Study 1: The Waterman “Can Opener”

For years, Bruce Rowley, a nearby business owner, has documented the predictable carnage at the Waterman Street railroad overpass, located near the Intrust Bank Arena. He calls it Wichita’s “truck-killing” bridge.

The math is simple: the bridge’s posted clearance is 12 feet, 0 inches. A standard semi-truck is 13 feet, 6 inches tall. The result is a steady stream of peeled-back roofs, particularly from rental trucks whose drivers are unfamiliar with the hazard. Each strike costs an estimated $10,000 to $15,000 to repair.

The City of Wichita is acutely aware of the problem. Its most visible response came in 2024, not with an engineering plan, but with a social media video. The video humorously explains that while geese and cars can fit, a 13.5-foot semi-truck “no it’s too tall”. This public relations effort implicitly frames the issue as one of driver error, placing the full burden of responsibility on operators to read the static signs.

This approach, however, is not a placeholder for a future fix. A review of the City of Wichita’s 2024-2033 Adopted Capital Improvement Program (CIP) confirms the bridge is conspicuously absent. There are no funded projects for the overpass , nor are there any in Sedgwick County’s CIP.

This lack of action is not for lack of opportunity. City construction bulletins show extensive, active redevelopment projects on the streets immediately adjacent to the bridge, including new sidewalks, aesthetic enhancements, and road reconfigurations on Commerce and St. Francis streets “from Waterman to Kellogg”.

The city is rebuilding the street around the hazard, but not the hazard itself. The cost of the “countless” crashes is borne not by the municipality, but by private trucking and rental companies.

Case Study 2: The North Side’s Legal and M_Rega-Gridlock

Twenty blocks north, the frustration is just as palpable, but the cause is profoundly different. Residents and commuters in North Wichita describe a “weekly occurrence” of severe traffic gridlock, where at-grade railroad crossings on 21st Street, 25th Street, and Broadway are blocked by stopped or slow-moving trains for hours at a time.

The impact transcends inconvenience; it’s a critical public safety risk, preventing police, ambulances, and firefighters from responding to emergencies.

But when citizens demand action, local officials are, in the words of Sedgwick County Commissioner Jim Howell, “generally powerless”.

The core issue is federal preemption. The Interstate Commerce Commission Termination Act (ICCTA), a federal law, grants the federal government exclusive jurisdiction over railroad operations. Federal courts have repeatedly used this act to strike down state and local laws attempting to regulate blocked crossings. The City of Wichita has no legal authority to fine or penalize BNSF or Union Pacific—the railways most cited in complaints—for blocking a crossing.

This legal impasse splits the issue into two distinct problems:

- The Operational Problem: Trains stopping on tracks. This is a logistics decision by the railroads, and the city is legally barred from intervening.

- The Engineering Problem: High-volume train and vehicle traffic sharing the same crossing. This is solvable through grade separation—building an overpass or underpass.

The public’s perception of “lack of concern” stems from the city’s inability to solve the first problem. But in reality, the city is deeply concerned with the second, which is why it’s the subject of a massive, multi-decade planning effort.

A Tale of Two Futures: No Fix vs. The “Big Fix”

When it comes to future plans, the contrast between the two bottlenecks is stark.

For the Waterman Street Bridge, the definitive outlook is the status quo. No projects are planned, funded, or proposed by the city or county to fix the 12-foot-clearance.

For the North Side Rail Conflict, the “lack of action” is a misperception. The problem is a top-tier regional priority, but its solution is enormous. The core of the plan is the “Area 2 – North Central” solution from the Wichita Railroad Master Plan. This “Big Fix” involves elevating 2.5 miles of BNSF track to eliminate at-grade crossings at 21st and 29th streets, at an estimated cost of $100 million.

A project of that magnitude is not yet funded for construction, but critical pre-construction steps are currently active and funded:

- A $1 Million study on the 21st Street corridor is underway to develop solutions that can successfully compete for large-scale federal construction grants.

- On October 1, 2024, the City Council approved a federal “Reconnecting Communities” Discretionary Pilot Grant , which provides the necessary planning funds to move the project from a “master plan” concept to a “shovel-ready” design.

- The Kansas Department of Transportation (KDOT) is coordinating its own major expansion of the K-96 corridor to include a new or improved interchange at 21st Street North , ensuring the two massive projects are compatible.

A Problem of Will

While Wichita officials battle federal law and nine-figure budgets for the rail-yard, other cities have successfully tackled their own “can openers” with far simpler solutions.

The most famous example, the “11foot8” bridge in Durham, North Carolina, was notorious for crashes. But unlike in Wichita, officials there implemented a two-pronged solution. They eventually raised the bridge by eight inches , but first, they installed an active Overheight Vehicle Detection System (OHVDS).

At a cost of approximately $150,000, this system uses a sensor to detect a tall truck and, most critically, triggers the adjacent traffic light to turn red. This forces the driver to stop and read a flashing “OVERHEIGHT MUST TURN” sign. The fix was highly effective, reducing crash frequency by over 70%.

According to a Texas DOT study, a single overheight bridge strike costs, on average, $200,000 to $300,000. One prevented crash would pay for the entire warning system.

For now, Wichita has chosen not to make that investment at Waterman. The city’s “lack of concern” is not uniform. It is a calculated decision—prioritizing other projects over a known hazard—a problem of will, not of law. As redevelopment continues downtown, drivers of tall trucks are left with one warning: a social media video and the sound of crunched metal from those who came before them.